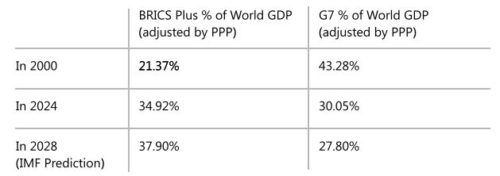

And now they are 10

Something significant happened on the 1st of January this year, the extension of BRICS.

The 5 founding members of the BRICS, namely Brazil, Russia, India, China & South Africa, have been joined by another five countries, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt & Ethiopia. The new coalition, now called the BRICS Plus, represent about 46% of the world population (3.7Bn), they produce about 43% of world crude oil.

Another 34 additional countries (map to right is illustrative, not fully up to date) have submitted an expression of interest in joining the EM bloc, which is also sometimes called the Global South.

The geographical distribution of the five countries invited to become members indicates the priorities of the BRICS in their future development strategies. The new members are located around major transport routes such as the Strait of Hormuz (Iran, UAE), the Red Sea (Saudi Arabia, “Ethiopia”), and the Suez Canal (Egypt), suggesting that the BRICS countries, are placing more emphasis than ever on the Middle East as a hub connecting Asia and Africa. The inclusion of Saudi Arabia and Iran in the same strategic alliance was probably only made possible by Beijing playing a key part brokering the restoration of ties in 2023 between the two longtime rivals.

From its full integration into Western-dominated globalisation at the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century, to its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) aimed at promoting Eurasian economic integration over the past decade, to the establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) and the BRICS mechanism, China has ultimately prioritised cooperation with Global South countries.

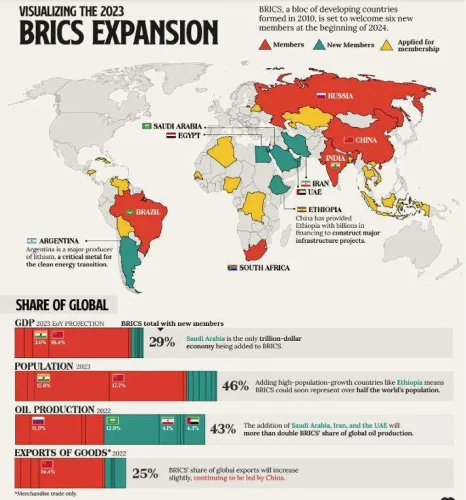

It is important to note that many of BRICS’ original members already have real GDP growth rates that are higher than their G7 counterparts, with the funding members having an average GDP growth of 189% to 2050 compared to the G7’s average of 50%, according to Goldman Sachs.

BRICS’ newly added members like Ethiopia (1,170% GDP growth projected by 2050) and Egypt (635% GDP growth projected by 2050) have even higher rates of potential economic growth, further raising the bloc’s economic potential.

Although the BRICS members do not have much in common on the surface, President Xi was trying to show his fellow bloc members that they all want a similar future: none of them want to live in a Western-dominated world.

The new cohort of countries join as BRICS pushes toward more diplomatic and financial coordination, including reform of the United Nations Security Council and a partial move away from a US dollar-dominated trade system.

There have been discussions of a potential BRICS currency (1) as part of a strategy of de-dollarization, the substitution of the dollar as the primary currency for international financial transactions. The U.S. trade war with China, as well as U.S. sanctions on China and Russia, are central to this ongoing discussion. Currently, about 90% of bilateral trade between China & Russia was conducted in rubbles and/or yuan and as of March 2024, over half (52.9%) of Chinese payments were settled in RMB while 42.8% were settled in U.S. dollars. At the ASEAN finance ministers and Central Banks meeting in Indonesia in March this year, policymakers discussed cutting their reliance on the U.S. dollar, the Japanese yen, and the Euro, moving to settlements in local currencies instead. In early April, Indian Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) had announced that India and Malaysia were starting to settle their trade in the Indian rupee. India already conducts most of its energy trade with Russia in Rupees or Rubbles and, when trading with the UAE, in Dirhams or Rupees. Early last year, Brazil and Argentina announced that they would begin allowing trade settlements in RMB. Until recently, nearly 100 percent of oil trading was conducted in dollars; however, in 2023, one-fifth of oil trades were reportedly conducted with non-dollar currencies. Russia’s deputy foreign minister revealed that the de-dollarization agenda would take center stage at the BRICS summit scheduled to take place in Russia in October 2024. The Russian delegation to China in June 2024 included the governor of the Central Bank, Elvira Nabiullina. Her participation was particularly noteworthy as she does not regularly

accompany Putin on overseas visits. However, her participation would have been crucial for any discussion regarding sanctions workarounds and Moscow’s interest in de-dollarization.

But rather than seeing the dollar replaced by a single currency, we are more likely to see a fragmentation of reserves as trade and investment are restructured to reflect an increasingly multipolar world. It may be easier to establish political consensus among the BRICS countries around a currency that coexists alongside the US dollar.

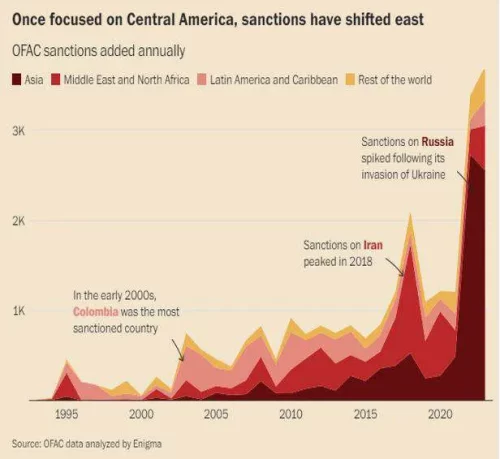

For some Nations, concerns about the U.S. range from uncertainty about political stability and policy continuity, to broader economic shifts related to great power competition. Mounting U.S. debt and domestic political contestation over budgets, debt limits and foreign policy are a headache for some governments around the world. For developing economies, particularly those with fixed exchange rates, the strength of the dollar in recent years has weakened the competitiveness of exports and raised the cost of servicing $-denominated debt. Another key aspect to keep in mind is that some EM Central banks also fret over the weaponization of the dollar through U.S. economic sanctions.

Western financial sanctions have frozen Russia’s foreign exchange reserves and confiscated the assets of some wealthy Russian citizens. These measures have triggered concerns in many countries about the risk of holding dollar-denominated assets. Another aspect of sanctions could be illustrated by the following saying “nature abhors a vacuum”. Prior to the international sanctions on Russia, Samsung and Apple’s joint share of the Russian mobile phone market was as high as 53 percent at the end of 2021 but fell to only 3 percent by the end of 2022. Meanwhile, the share of Chinese mobile phones in the Russian market rose from 40 percent at the end of 2021 to 95 percent at the end of 2022.

The West’s weaponisation of the US dollar has prompted Global South countries to pursue local currency settlements, a dynamic that will likely upend the dollar-dominated system of international trade settlements and payments, weaken the dollar’s status as the key global currency, and reshape the international financial order in the years to come. De-risking’ is replacing ‘decoupling’ as the key word to describe today’s international political and economic hotspots. Whether it is the de-risking of China and Russia by the West or the de-risking of the West by the Global South countries, the common feature is the weakening of the existing Western-dominated international economic order and the promotion of a more multipolar world. The refusal of developing countries to align with Western policy on the war and sanctions against Russia has led to increasing discourse on the Global South’s political role on the international stage.

The balance of power between the West and the Global South countries today is very different from the balance that existed during the Cold War between the West and the former Soviet bloc. Technological development will be a critical enabler of local currency settlements for Global South countries in the future.

Sanctions are overwhelmingly a tool of the U.S. In the second half of the twentieth century, the U.S. had a near monopoly on the aggressive use of the economic instrument to achieve its objectives. Studies noted that in 202 sanctions episodes from the end of World War II up through 2000, the U.S. was a “sanctioner” in 140 of these episodes and has imposed sanctions with similar frequency since 2000. According to a report put out last year by the Washington-based Centre for Economic and Policy Research, one in three countries around the world face some form of US sanctions of varying intensity.

In recent years, a secondary phenomenon has emerged and greatly extended the scope of U.S. sanctions. For some time, the phenomenon was referred to as a “chilling effect” and more recently has come to be referred to as “overcompliance.” Overcompliance is the result of two conditions: First, the due diligence requirements for compliance with the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) regulations are not fully explicit. For example, key terms such as “material support” are not consistently and explicitly defined, and OFAC has very often declined to provide sufficient clarity to private actors. Second, the penalties for running afoul of U.S. sanction are severe. Most notably, BNP Paribas paid near USD 9billions in penalties and was temporarily and partially suspended from the Federal Reserve. The result was a “chilling effect” throughout the international banking community. The combination of these factors drives the risk assessment of banks globally, and they broadly arrive at similar decisions: to withdraw from entire markets that are viewed as high risk, which is the case for many Global South countries. Banks are seeking not only to comply with Treasury Department regulations, but in fact go well beyond them, foregoing even legal business opportunities, to minimize their risk in the face of the uncertainties surrounding OFAC’s enforcement practices and the high costs of potential enforcement. Major international banks, with increasing frequency, decide that it is not worth it to have a presence in these countries or regions, and withdraw from the Global South market in large numbers. Banks also terminate correspondent bank relations (CBRs). Correspondent banks are intermediaries that provide an array of services, such as facilitating cross-border transactions. The termination of CBRs affects not only remittances, but also many of a country’s critical economic functions, such as receiving payments for exports, sending payment for imports, foreign investment, and access to capital markets.

The US global sanctions regime, as maverick US Republican Senator Rand Paul has argued, has become a substitute for skilful diplomacy and a well-crafted US foreign policy. That could ultimately be self-defeating.

To be sure, talk of de-dollarisation isn’t new. Questions about the dollar’s dominance arose when the Bretton Woods system fell apart, when the European Union launched the Euro in 1999 and then again after the 2008-2009 financial crisis. The dollar’s dominance survived those storms. Today, about 57% of foreign exchange reserves maintained by the world’s central banks are held in dollars. Still, that marks a decline from about 70% in 2000. The dollar’s dominance is unlikely to change in the near future. But its stranglehold on the global financial system could weaken if more countries start trading in other currencies and reduce their exposure to the dollar. The sustainability of the U.S. Government Debt will force hard choices in the future (we will cover that in detail in a future paper).

Defenders of the US like to argue that dollar dominance is here to stay because there is no alternative currency to compete for the greenback’s premier reserve currency status and as the essential currency in world trade. But they are arguing from the standpoint of US power, not its legitimacy, which is increasingly difficult to defend. The dollar has been the source of unprecedented US power, it might become its Achilles’ heel. Other people might have once been happy to go along because they enjoyed the benefits of global trade. But many of those benefits have turned into unpredictable risk or even outright threats, thanks to what has been called “how America weaponised the world economy”.

Western politicians frequently repeat the phrase « rules-based international order. » However, their actions often contradict their words, as evidenced by their willingness to confiscate a sovereign state’s assets. The rules-based order only works if those who promote it follow the same rules and norms they impose on others.

Some economists advise for a BRCIS currency to use gold price as a reference value, when other economists are saying that it would be preferable to build a BRICS currency as a basket of currencies, similar to the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights.

An initial BRICS currency will not be used for personal consumption but only for international trade settlements. A BRICS currency might be launched as a digital currency, and if not, different central banks within BRICs are developing alternative cross-border payment system to SWIFT (mBridge).

Disclaimer The law allows us to give general advice or recommendations on the buying or selling of any investment product by various means (including the publication and dissemination to you, to other persons or to members of the public, of research papers and analytical reports). We do this strictly on the understanding that: (i) All such advice or recommendations are for general information purposes only. Views and opinions contained herein are those of Bordier & Cie. Its contents may not be reproduced or redistributed. The user will be held fully liable for any unauthorised reproduction or circulation of any document herein, which may give rise to legal proceedings. (ii) We have not taken into account your specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs when formulating such advice or recommendations; and (iii) You would seek your own advice from a financial adviser regarding the specific suitability of such advice or recommendations, before you make a commitment to purchase or invest in any investment product. All information contained herein does not constitute any investment recommendation or legal or tax advice and is provided for information purposes only.

In line with the above, whenever we provide you with resources or materials or give you access to our resources or materials, then unless we say so explicitly, you must note that we are doing this for the sole purpose of enabling you to make your own investment decisions and for which you have the sole responsibility.

© 2024 Bordier Group and/or its affiliates.